The Secrets of the Mantón de Manila with Paula Rodríguez Lázaro

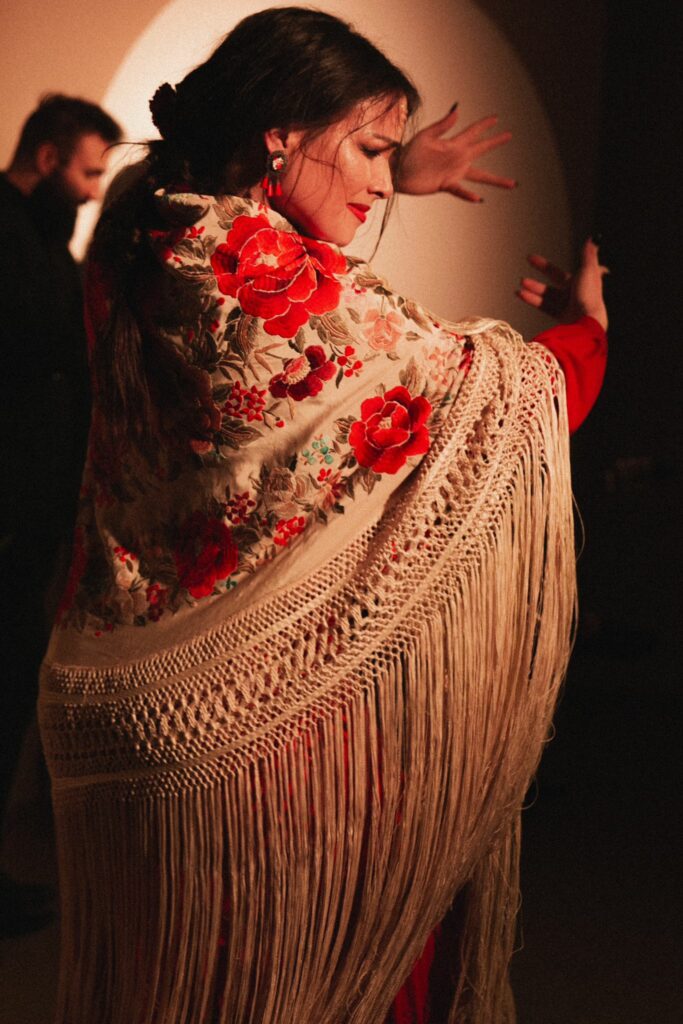

There are moments on the stage of Tablao Flamenco 1911 that take your breath away. One of them is, without a doubt, when a bailaora makes the Mantón de Manila fly. That cascade of silk and fringes that becomes wings, a cape, a whirlwind of color… it’s pure flamenco magic! But that flight doesn’t come from nowhere; it demands a mix of strength and delicacy that is an art in itself.

We are privileged to have an artist who masters it like few others: Paula Rodríguez Lázaro. That’s why we sat down with her here, on the storied stage of our centennial venue, to uncover the secrets hidden in each of those flights.

What does the mantón mean to you?

Let’s get to the heart of it, Paula. For those of us sitting down, we see a beautiful piece of fabric flying. But for you, who live it from within, what really is the mantón? An extension of your body, a weight to tame, another voice in your dance?

“The mantón is an element full of tradition. As a bailaora, it enriches me, gives me confidence and freedom. It brings color, character, and a very different movement to my dance. It is, without a doubt, an extension of my body. Its movement must fully adapt to the dancer’s body and choreography: to her shape, her form, her energy… Sometimes it should flow gently; other times, it must fly with strength or even aggressiveness. It all depends on what you want to express.”

Is the mantón still relevant today?

Of course — because that image of the mantón is so powerful that it sometimes seems anchored in the past. Does it still have something to say today? Or does it run the risk of becoming a cliché if not handled with the truth of today’s flamenco?

“I believe we, as bailaoras, are very aware of the importance of the mantón—not letting it be forgotten and continuing to use it as part of our tradition and culture. It’s true that we still carry a slightly old-fashioned image: that of women with the mantón draped over their shoulders. Even so, in the world of dance, the mantón has its place, its recognition, and—above all—is deeply respected because it’s one of the most complex elements to master.

Of course, it still has a lot to say today. It’s an image deeply rooted in tradition and culture—not just Spanish, since the mantón has Eastern origins—which gives it even more richness. But what’s most interesting is that today it’s being redefined: it’s no longer just a decorative garment to enhance appearance, but also a technical and expressive resource that brings new qualities and movement possibilities to the dance. These may not be orthodox forms, but they are truly original, creative, and very relevant.”

Dancing with the mantón at Tablao Flamenco 1911

Here at Tablao 1911, with the closeness of the audience, does it feel different to dance with the mantón? Does it allow the details of the movement, the embroidery, to be better appreciated?

“The stage at Tablao 1911 is very large and spacious, which allows you to move freely and make full use of the space. Added to that is the closeness of the audience, which is quite unique — you can even feel the cold air stirred by the mantón as it moves. Sometimes I take such risks dancing near the edge of the stage that the fringes brush over the heads of the guests. It’s definitely something very special.”

In which palos do you enjoy the mantón the most?

Are there flamenco palos where you especially enjoy using the mantón here at 1911? Maybe some Alegrías, a Caña…? Why?

“Honestly, I use the mantón in almost every palo, because I love exploring different ways of interpreting it. Alegrías with bata de cola and mantón is the most traditional, of course, but when you use it in a Soleá, for example, the movement and the energy it creates are completely different… and I love that. Lately, for Alegrías, I’ve been using the fan more than the mantón, but if it’s paired with a bata de cola, I adore it. I use it a lot in the Caña — I really love it — and lately I’ve been exploring Tientos as well, and I’m very excited about that too.”

The technique behind the flight

Dancing with a mantón requires a very specific technique, right? What is the most difficult thing to master so that the mantón “flies” with that apparent ease?

“I love this question, because I think many people, when they see you dancing with the mantón, believe it all depends on arm and chest strength… and it really doesn’t. I, for example, have strong legs, but not so much upper body strength. And the mantón doesn’t require force. In fact, if you see a bailaora using too much strength to move it, she probably doesn’t have much technique.

The mantón demands precision: knowing how to place your hand correctly and using your own body movement in favor of the mantón. That’s where a technical, elegant, and beautiful flight is truly achieved. If it’s forced too much, it’s likely being misused.”

Any special mantón in your collection?

We’ve seen some stunning mantones. Do you have a special or favorite one in your personal collection? Any story behind any of them?

“My favorite mantón is, without a doubt, the one I used to win the prize for best female desplante in 2021 at Las Minas. It cost me a fortune, but it made me incredibly happy, and I’ll keep it in my wardrobe forever. I’ve sold many, dyed others… I remember a beautiful white one I used so much it couldn’t even be washed anymore, so I dyed it black and pale pink. Many mantones have passed through my hands — some ended up with my students — but that one, in particular, is very special to me.

And beyond the personal, there’s a mantón we all think of when we talk about flamenco history: Blanca del Rey’s. She used it in her Soleá. It’s a true work of art — majestic, stunning. A black mantón with beige fringes, almost off-white… It’s an iconic piece and a reference for all bailaores.”

Advice for the audience

From the perspective of the audience who comes to 1911, what details of dancing with the mantón would you recommend we pay attention to in order to appreciate it better?

“I think the audience would be surprised to know how much a mantón actually weighs. Many say, ‘that must be heavy,’ but when they hold it, they don’t expect it to be that heavy. That’s why my first recommendation is to enjoy it — to observe its movement, but also to notice the technical difficulty behind it.

Dancing with a mantón involves a lot of risk: it can get caught anywhere, often in the most unexpected places… a hairpin, an earring, a flower, a small nail on the floor, even a wooden beam in the ceiling. It’s an imposing element that demands attention and respect.”

Dancing with history and tradition

As an artist who is part of the cast of this historic tablao, what do you feel when dancing with such a traditional element as the mantón on a stage as iconic as the old Villa Rosa?

“When I dance as part of the Tablao 1911 cast, performing on this historic stage —with or without the mantón— is a true privilege and a great responsibility. Many important artists have performed here, and being part of that history is a huge honor.

Also, the Mantón de Manila really shines in this space. The tiles, the paintings… the entire setting transports you to another era, to those times when women wore the mantón with such natural elegance. That’s why this stage is a special place to use it — it truly stands out.”

The emotion the mantón conveys

To end, what emotion or feeling do you seek to transmit to the audience at Tablao 1911 when you dance with the mantón?

“When I dance with the mantón at 1911, my biggest wish is that the audience ends up falling in love with the mantón… and with my dancing. Many times, after the show, they tell me: ‘I loved what you did with the scarf.’ And I always reply: ‘It’s called a mantón.’ Because many people don’t know the tradition and history behind it.

With deep respect for the audience, for dance, and for art, I try to convey that love and emotion that can be awakened when watching a bailaora move a mantón full of cultural weight. It’s a gesture rooted in the past, and it has soul.”

Don’t miss the magic of the Mantón de Manila with Paula Rodríguez Lázaro at Tablao Flamenco 1911.

Book your tickets here and experience a night full of emotion and art. We’re waiting for you!